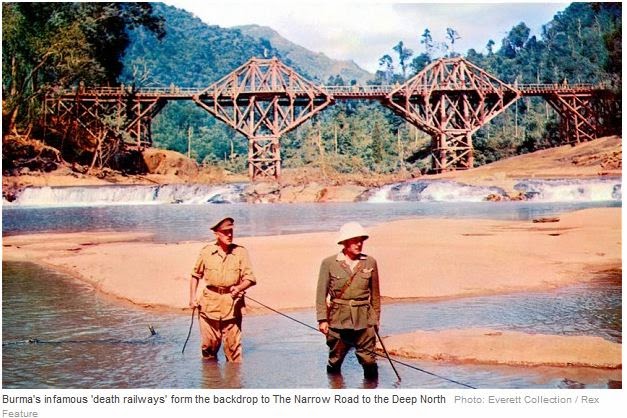

The Narrow Road to the Deep North - Richard Flanagan

==========================================

****1/2

(Man Booker Award Winning novel 2013 )

"A Happy Man has no past, while an unhappy man has

nothing else" (From " The Narrow Road to the Deep North")

Writing an essay called

"Freeing My father", for the

Sydney Morning Herald, Flanagan says that his father totally forgot about his time as a Prisoner of War (PoW),

upon his son's account of meeting and conversing with some of the men of the

Japanese Imperial Army, under whom his father was a PoW, back in 1942-43, in

then Siam. Flanagan Snr. was 98 at the time that his son spoke to his father's

former Prison officials, and soon after, passed away towards the tail end of

completion of this book. I read this essay, as is my wont, two days after

reading the booking - a time during which I randomly read sections of the book,

read reviews, write sentiments about the book, in a notebook I keep especially

for that purpose, and meander in and out of the world of the tale. And I

thought that this is a book, worthy of a meandering.

The author says that he wanted

his book to be based on a romance, ever though although very much a war tale.

The Romance is there for all to see - the protagonist's affair with his uncles' young wife. It is a

tale of interest and has significance within the novel - yet, the romance ended up in the periphery of the novel. It is

in the periphery, along with most of Dorrigo Evans' (the protagonist) pre-war

life, and his post-war life. True that his war time experience made him the man

he was, a war hero, a famous surgeon, a public figure and an uninterested,

cheating husband and an almost a passive father - ( until a moment arises in

which, he is to prove himself in the face of a life threatening incident to his family. And for a second time, cometh the

hour, and rises the man! ) This then, this rising to be a man beyond his own

expectations is the part that captured my

interest most about this novel, most. The Protagonist is a man with many

failings, but all throughout, "the big fella", the leader

to a thousand Australian prisoners of war slaving in the "death

railway" in Siam, he rises above his usual self, just as the men around

him expect it of him. This then, is a

leader born at the moment. In everyday life he had no place for virtue. "Virtue was vanity dressed up and waiting

for applause", believed Evans. "... Dorrigo Evans understood himself as a weak man who was entitled to

nothing, a weak man whom the thousand were forming into the shape of their

expectations of him as a strong man. It defied sense. They were captives of the

Japanese and he was the prisoner of their hope."(excerpt) It is this expectation, which he tried to

fulfill during that period, from April 1942 to September 1943, in a stretch

building the Burmese death Railway under the Japanese Imperial Army. They had

to do this under minimum tools, no medication, torrential rains, starvation and

all sorts of diseases - malaria, dengue, dysentery, topical ulcers and the

dreaded cholera. The horror that this combination brings about is absolutely

harrowing.

"The Horror! The Horror!" - this is the weak whisper that

Marlow hears as Kurtz dies, in Conrad's seminal work, "heart of darkness".

However much a great read "heart of darkness" was, I always felt that

Conrad did not sufficiently capture this horror, that he hinted of. In

contrast, it is horror that defines this

novel. Hence my argument that the romance is just in the borders.

Following is an excerpt of

Dorrigo Evans operating on Jack Rainbow, whose leg has already been amputated

twice.

"There was noise from the general hospital huts but it was almost

immediately drowned out by jack's screaming as Dorrigo Evans began cutting away

his leg stump. The stench of the dead flesh was so powerful it was all he could

do not to vomit......But there was really no leg left to get, only a weirdly moving and bloody thing that seemed just want to be left alone. The tiny piece of thigh that remained was now so slippery with blood that it was very difficult to work on....

With each galvanic jolt blood was

spewing out in a small fountain. It was as if Jack Rainbow's body were

willingly pumping itself dry. Dorrigo Evans was trying to stitch as far up the

artery as he could go, the blood was still galloping out, Squizzy Taylor was

unable to staunch the flow, blood was everywhere, he was desperately trying to

think of something that might buy some time but there was nothing. He was

stitching, the blood was pumping, there was no light, the stitches kept

ripping, nothing held.

Push harder, he was yelling to

Squizzy Taylor. Stop the f...ing flow.

But no matter how hard Squizzy

Taylor pushed, still the blood kept surging, spilling over Dorrigo Evans' hand

and arm, running down into the Asian mud and the Asian morass that they could

not escape, that Asian hell that was dragging them all ever closer to itself."

This, in a

makeshift thatched hut functioning as

the operating theater, with a kitchen saw as the cutting tool, and a

soup ladle forced upon the femoral artery to stop the blood flow!

Then there

was the Benjo! "... the benjo was a

trench twenty yards long and two and a half yards deep, over which the men

precariously squatted on slimy bamboo planking to relieve themselves. The

bobbing excrement below was covered with writhing maggots-like desiccated

coconut on lamingtons, as Chum Fahey said. It was a vile horror. When the

prisoners competed in devising ways of doing in their most hated guard, they

joked of one day drowning the Goanna in the benjo. Even for them, a more

terrible death was hard to conceive." It is in this hell that Darky

Gardiner, hinted as the illegitimate son of Dorrigo's brother, Tom (he gets to

know of it only upon his return drowns

in, trying to relieve himself after a beating that lasted for many hours. (He is beaten because some of the

men in his work group had absconded work, and he was in charge of the

work group that day.)

" THEY FOUND HIM late that night. He was

floating head-down in the benjo, the long, deep trench of rain-churned shit

that served as the communal toilet. Somehow he had dragged himself there from

the hospital, where they had carried his broken body when the beating had

finally ended. It was presumed that, on squatting, he had lost his balance and

toppled in. With no strength to pull himself out, he had drowned....

Oh, you f...ing stupid bastard,

Darky. Couldn't you just have shat yourself on the bunk like every other dopey

bugger? Couldn't you just have folded their f...ing blanket the right way out?

As they raised Darky Gardiner's

body, Jimmy Bigelow glimpsed it by the light of the kerosene lantern. Coated in

maggots, it was something so oddly bruised, crushed, filthy, so dirty and

broken, that for a moment he thought it could not be him."

By the way,

relieving themselves where they were was acceptable, in this dysentery

infested, cholera weakened prisoner camp, as can be understood by Jimmy's

lamentations against his deceased colleague. This then is a glimpse to the

unfathomable horror enclosed within these pages. But then, it is not my objective

to portray the Japanese as evil, in a literal sense. Thus I continue.

Major Nakamura is the commanding

officer from JIA, and this is what he has to say in one of his exchanges with

Dorrigo, via a translator. Further it can be easily understood that it is this

Nakamura, albeit with a different name that the author met in his trip to Japan,

in the essay which I referred to, at the beginning."It is true this war is cruel, Lieutenant Fukuhara translated. What war is not? But war is human beings. War what we are. War what we do. Railway might kill human beings, but I do not make human beings. I make railway. Progress does not demand freedom. Progress has no need of freedom. Major Nakamura, he say progress can arise for other reasons. You, doctor, call it non-freedom. We call it spirit, nation, Emperor. You, doctor, call it cruelty. We call it destiny."

It is clear that the JIA had an embodiment of the concept of Japan, the Emperor, and the Japanese spirit and even their own death against this belief is not too great a price. So much so they literally treat prisoners of war as being less than human, since they surrendered (against killing themselves). In Nakamura's own mind he is a good man, for he felt the pain as Darky Gardiner was beaten out of sense, as a result of his order for punishment, but he sees no alternative . Either he has to deliver the railway, or kill himself in shame. This is the same man, who abstains from even killing a mosquito, later in life, now settled with a wife and kids. I felt that war is unfathomable. The horror of war is something that arises out of the conditions, circumstances and higher orders that make the "men in the field" act in a particular manner. For those who are involved in the very midst of it, at that precise moment, they believe that they are doing the best they could. Nakamura firmly believed in it, in his circumstances. Dorrigo Evans firmly believed it given his circumstances. And I honestly feel that people who decide and judge these men who were made to war, a war fed, groomed and declared by those who are never on the battle field, are much worse than those men who had the heat of the war in their hands, which largely forced them act in the way they did. For it is these men, who are miles away from the horror and the filth of war, but are the very ones to declare the next war. Then how much credibility can their judgment on who is a war criminal and who is not, carry ? I can't help, but be reminded of Bob Dylan's words....

Come you masters of war

You that build all the guns

You that build the death planes

You that build all the bombs

You that hide behind walls

You that hide behind desks

I just want you to know

I can see through your masks.

You fasten all the triggers

For the others to fire

Then you set back and watch

When the death count gets higher

You hide in your mansion'

In this

novel, we have a Korean guard of the prisoners, who had joined the Japanese

army solely due to the stipend of 50 yen, and whatever actions he carried out

were are under the orders of his superior, Maj. Nakamura. He is given the death

sentence by an Australian Court after Japanese surrender, and until his death

he cannot think of anything else, but the 50 yen, the promised stipend which he

is yet to receive. It is at the trial that he understands the Geneva

convention, the chain of command and the military structure of the Japanese -

this then is a so called "war criminal" who pays the ultimate price

for his "atrocities", undoubtedly in which he part took in. Yet, Maj,

Nakamura, having gone to the Japanese mainland, forges a new identity and lies

low until the anti-Japanese mood changes sufficiently. When it does change, the

Americans are now friends with Japanese, and have adopted the philosophy of

"let bygones be bygones" and that of "forgiving and

forgetting", for most diabolical of reasons. In an exchange many years

after the war, between Nakamura and another doctor who part took in the war, Sato,

we are told that: " Mr. Naito was one of the leaders

of our very best scientists in similar work there. Vivisection. And many other

things. Testing biological weapons on prisoners. Anthrax. Bubonic plague, too,

I am told. Testing flamethrowers and grenades on prisoners. It was a large

operation with support at the highest levels. Today Mr. Naito is a

well-respected figure. And why? Because neither our government nor the

Americans want to dig up the past. The Americans are interested in our biological

warfare work; it helps them prepare for war against the Soviets. We tested

these weapons on the Chinese; they want to use them on the Koreans. I mean, you

got hanged if you were unlucky or unimportant. Or Korean. But the Americans

want to do business now."

Here we see,

what a farce the whole thing is, and it is the misguided, the gullible, those

with their own political objectives and of course those out with a vendetta who

seek redress through trials, in a post war environment. For almost always, the

true guilty can never be judged, in a post war environment. For one thing the

question remains as to who the true guilty is, and for another the judges try to

judge the happenings on a battlefield that is almost beyond comprehension, for

those who took no part in it. In this respect, other than attempting to avoid

war by all possible means, seeking justice in a post-war environment appears

largely, to do a second wrong in a futile effort to put right what could've

been an initial wrong.